Multiple Myeloma

Overview

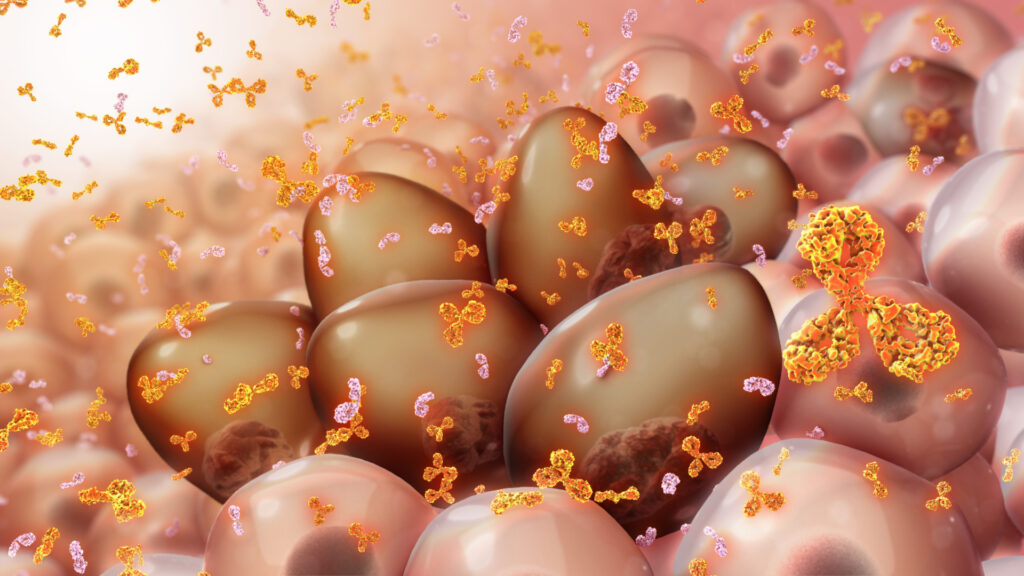

Multiple myeloma is a cancer that forms in a type of white blood cell called a plasma cell. Healthy plasma cells help you fight infections by making antibodies that recognize and attack germs.

In multiple myeloma, cancerous plasma cells accumulate in the bone marrow and crowd out healthy blood cells. Rather than produce helpful antibodies, the cancer cells produce abnormal proteins that can cause complications.

Treatment for multiple myeloma isn’t always necessary right away. If the multiple myeloma is slow growing and isn’t causing signs and symptoms, your doctor may recommend close monitoring instead of immediate treatment. For people with multiple myeloma who require treatment, a number of options are available to help control the disease.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of multiple myeloma can vary and, early in the disease, there may be none.

When signs and symptoms do occur, they can include:

- Bone pain, especially in your spine or chest

- Nausea

- Constipation

- Loss of appetite

- Mental fogginess or confusion

- Fatigue

- Frequent infections

- Weight loss

- Weakness or numbness in your legs

- Excessive thirst

Causes

It’s not clear what causes myeloma.

Doctors know that myeloma begins with one abnormal plasma cell in your bone marrow — the soft, blood-producing tissue that fills in the center of most of your bones. The abnormal cell multiplies rapidly.

Because cancer cells don’t mature and then die as normal cells do, they accumulate, eventually overwhelming the production of healthy cells. In the bone marrow, myeloma cells crowd out healthy blood cells, leading to fatigue and an inability to fight infections.

The myeloma cells continue trying to produce antibodies, as healthy plasma cells do, but the myeloma cells produce abnormal antibodies that the body can’t use. Instead, the abnormal antibodies (monoclonal proteins, or M proteins) build up in the body and cause problems such as damage to the kidneys. Cancer cells can also cause damage to the bones that increases the risk of broken bones.

A connection with MGUS

Multiple myeloma almost always starts out as a relatively benign condition called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).

MGUS, like multiple myeloma, is marked by the presence of M proteins — produced by abnormal plasma cells — in your blood. However, in MGUS, the levels of M proteins are lower and no damage to the body occurs.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of multiple myeloma include:

- Increasing age. Your risk of multiple myeloma increases as you age, with most people diagnosed in their mid-60s.

- Male sex. Men are more likely to develop the disease than are women.

- Black race. Black people are more likely to develop multiple myeloma than are people of other races.

- Family history of multiple myeloma. If a brother, sister or parent has multiple myeloma, you have an increased risk of the disease.

- Personal history of a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Multiple myeloma almost always starts out as MGUS, so having this condition increases your risk.

Complications

Complications of multiple myeloma include:

- Frequent infections. Myeloma cells inhibit your body’s ability to fight infections.

- Bone problems. Multiple myeloma can also affect your bones, leading to bone pain, thinning bones and broken bones.

- Reduced kidney function. Multiple myeloma may cause problems with kidney function, including kidney failure.

- Low red blood cell count (anemia). As myeloma cells crowd out normal blood cells, multiple myeloma can also cause anemia and other blood problems.

Diagnosis

Sometimes multiple myeloma is diagnosed when your doctor detects it accidentally during a blood test for some other condition. It can also be diagnosed if your doctor suspects you could have multiple myeloma based on your signs and symptoms.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose multiple myeloma include:

Blood tests. Laboratory analysis of your blood may reveal the M proteins produced by myeloma cells. Another abnormal protein produced by myeloma cells — called beta-2-microglobulin — may be detected in your blood and give your doctor clues about the aggressiveness of your myeloma.

Additionally, blood tests to examine your kidney function, blood cell counts, calcium levels and uric acid levels can give your doctor clues about your diagnosis.

- Urine tests. Analysis of your urine may show M proteins, which are referred to as Bence Jones proteins when they’re detected in urine.

Examination of your bone marrow. Your doctor may remove a sample of bone marrow for laboratory testing. The sample is collected with a long needle inserted into a bone (bone marrow aspiration and biopsy).

In the lab, the sample is examined for myeloma cells. Specialized tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) can analyze myeloma cells to identify gene mutations.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests may be recommended to detect bone problems associated with multiple myeloma. Tests may include an X-ray, MRI, CT or positron emission tomography (PET).

Assigning a stage and a risk category

If tests indicate you have multiple myeloma, your doctor will use the information gathered from the diagnostic tests to classify your disease as stage I, stage II or stage III. Stage I indicates a less aggressive disease, and stage III indicates the most aggressive disease.

Your multiple myeloma may also be assigned a risk category, which indicates the aggressiveness of your disease.

Your multiple myeloma stage and risk category help your doctor understand your prognosis and your treatment options.

Treatment

If you’re experiencing symptoms, treatment can help relieve pain, control complications of the disease, stabilize your condition and slow the progress of multiple myeloma.

Immediate treatment may not be necessary

If you have multiple myeloma but aren’t experiencing any symptoms (also known as smoldering multiple myeloma), you might not need treatment right away. Immediate treatment may not be necessary for multiple myeloma that is slow growing and at an early stage. However, your doctor will regularly monitor your condition for signs that the disease is progressing. This may involve periodic blood and urine tests.

If you develop signs and symptoms or your multiple myeloma shows signs of progression, you and your doctor may decide to begin treatment.

Treatments for myeloma

Standard treatment options include:

- Targeted therapy. Targeted drug treatments focus on specific weaknesses present within cancer cells. By blocking these abnormalities, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy uses your immune system to fight cancer. Your body’s disease-fighting immune system may not attack your cancer because the cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from the immune system cells. Immunotherapy works by interfering with that process.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. The drugs kill fast-growing cells, including myeloma cells. High doses of chemotherapy drugs are used before a bone marrow transplant.

- Corticosteroids. Corticosteroid medications regulate the immune system to control inflammation in the body. They are also active against myeloma cells.

Bone marrow transplant. A bone marrow transplant, also known as a stem cell transplant, is a procedure to replace your diseased bone marrow with healthy bone marrow.

Before a bone marrow transplant, blood-forming stem cells are collected from your blood. You then receive high doses of chemotherapy to destroy your diseased bone marrow. Then your stem cells are infused into your body, where they travel to your bones and begin rebuilding your bone marrow.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy beams from sources such as X-rays and protons to kill cancer cells. It may be used to quickly shrink myeloma cells in a specific area — for instance, when a collection of abnormal plasma cells form a tumor (plasmacytoma) that’s causing pain or destroying a bone.